Table Of Content

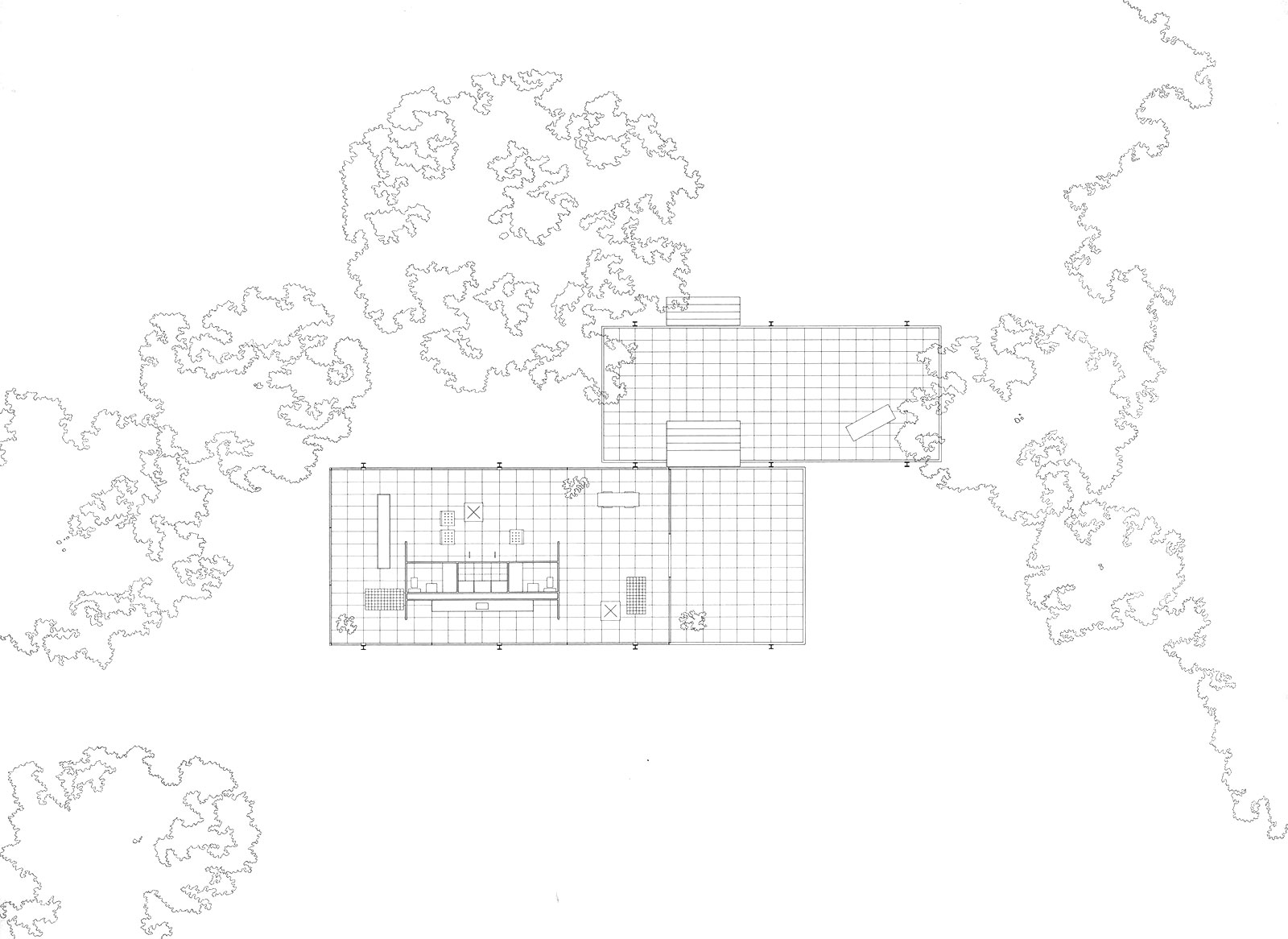

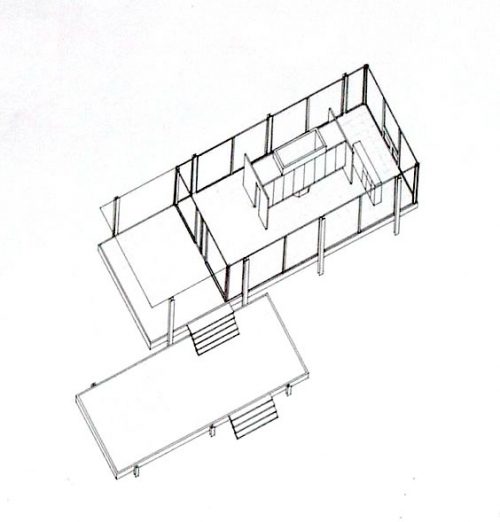

Two distinctly expressed horizontal slabs, which form the roof and the floor, sandwich an open space for living. The house is elevated 5 feet 3 inches (1.60 m) above a flood plain by eight wide flange steel columns which are attached to the sides of the floor and ceiling slabs. A third floating slab, an attached terrace, acts as a transition between the living area and the ground. The house is accessed by two sets of wide steps connecting ground to terrace and then to porch.

The absence of walls

The Farnsworth House is renamed to honor Edith Farnsworth - The Architect's Newspaper

The Farnsworth House is renamed to honor Edith Farnsworth.

Posted: Tue, 19 Oct 2021 07:00:00 GMT [source]

The windows are what provide the beauty of Mies' idea of tying the residence with its tranquil surroundings. His idea for shading and privacy was through the many trees that were located on the private site. Mies created a 1,500-square-foot (140 m2) structure that is widely recognized as an exemplar of International Style of architecture. The retreat was designated a National Historic Landmark in 2006, after being listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2004.[5] The house is owned and operated as a house museum by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. During the late nineteenth century, Plano and the Fox River environs were considered a “beauty spot,” attracting travelers and new residents – including several gentleman farmers and weekend cottagers. No doubt Edith Farnsworth was aware of the area’s rural character and natural scenery when, in 1944, she discovered the site of her future weekend house.

River Views

She purchased tables by Florence Knoll, chairs by Bruno Mathsson and Jens Risom, many of which were likely sourced from Baldwin Kingrey, the Chicago-based furniture store owned by Kitty Baldwin Weese and Jody Kingrey Albergo. She fought to retain the house that she’d envisioned, and after years of legal turmoil, she did. The two would visit the site frequently for picnics with the young architects who worked in Mies’ office, and even the office accountant, Felix Bonnet, from 1946, when design began, through 1949, when construction started. And, as Farnsworth became busier, publishing and presenting her research at conferences, the architects in Mies’ office would draw her charts and visualize her data for her. The two shared a friendship and an intimacy that, from a historical perspective, is difficult to define.

An Emerging, Evolving, Energized Edith Farnsworth House: A Q&A with Scott Mehaffey

With the Farnsworth house constructed about 100 feet from the Fox River, Mies recognized the dangers of flooding. He designed the house at an elevation that he bellieved would protect it from the highest predicted floods, which are anticipated every hundred years. "If you view nature through the glass walls of the Farnsworth House, it gains a more profound significance than if viewed from the outside. That way more is said about nature—it becomes part of a larger whole."

The architecture of the house represents the ultimate refinement of Mies van der Rohe’s minimalist expression of structure and space. It is composed of three strong, horizontal steel forms – the terrace, the floor of the house, and the roof – attached to attenuated, steel flange columns. Mies intended for the house to be as light as possible on the land, and so he raised the house 5 feet 3 inches off the ground, allowing only the steel columns to meet the ground and the landscape to extend past the residence.

This is one of the principal reasons why the house was built elevated above the ground. Mies, according to Mehaffey, “did what he could to keep that story going about her.” Because he was one of the great architects of the 20th century — and a man — his version of the story prevailed. Born in 1903 to a wealthy Chicago family and brought up on Astor Street, she got her medical degree from Northwestern University in 1938, at a time when very few women were doctors. In 1942, the Tribune wrote of her and one other woman doctor, saying it was “a curious thing that purlieus of upper Astor Street [would] burst the bonds of social life” to go into medicine, a man’s profession.

Casa Bloc Museum-Apartment

Outdoor living spaces were designed to be extensions of the indoor space, with an open terrace and a screened porch (the screens have been removed). Yet the synthetic element always remains clearly distinct from the natural by its geometric forms that are highlighted by the choice of white as their primary color. Farnsworth had purchased the wooded, nine-acre riverfront property from the publisher of the Chicago Tribune, Robert R. McCormick. Mies developed the design in time for it to be included in an exhibition on his work at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1947.[9] After completion of design, the project was placed on hold awaiting an inheritance from an ailing aunt of Farnsworth. The commission was an ideal one for any architect, but was marred by a very publicized dispute between Farnsworth and Mies that began near the end of construction. A cost overrun of $15,600 over the initially approved construction budget of $58,400, was due to escalating material prices resulting from inflationary commodities speculation (in anticipation of demand arising from the mobilization for the Korean War).

migrant couples got married in Chicago: See the prep, ceremony and wedding party

Drains and pipes pass through the floor and a vertical shaft which contains the bathroom vents and the chimney flue travels through the roof and exit the exterior, also allowing access for services such as electricity and water. These utilities are concealed, built in the most discrete and inaccessible areas of the slabs, becoming almost as invisible in the interior as the exterior of the house. The white-painted, sandblasted steel frame—with welds sanded away to render attachments invisible—contrasts with its natural setting, becoming an object of Platonic perfection, seemingly more idea than reality. Far from a static, isolated object, the sliding horizontals of the house and terraces reach out and engage their natural setting, offering a contrast to emphasize the rich colors and natural forms of the seasonally changing riparian prairie. Mies served as General Contractor on the project, and his innovative details and iron-willed vision proved costly.

His mature design work is a physical expression of his understanding of the modern epoch. He provides the occupants of his buildings with flexible and unobstructed space in which to fulfill themselves as individuals, despite their anonymous condition in the modern industrial culture. Mies accepted the problems of industrial society as facts to be dealt with, and offered his idealized vision of how technology may be made beautiful and support the individual as well. He suggests that the downsides of technology decried by late nineteenth century critics such as John Ruskin, can be solved with human creativity, and shows us how in the architecture of this house. Alongside steel, wrought iron, and concrete, the material came to define an architectural movement and quickly captured architects’ imagination. Glass structures—with their lightness, transparency, translucency, and reflectivity—intimately reveal their interiors and provide a commune with nature that was previously unachievable.

The proportions of the floor, the positioning of the pillars, the porch area and the mullions of the carpentry of the enclosed space are conditions which remain invariable. The architect proposed that the interior distribution had to encompass all the functional requirements, installations, bathrooms and kitchen without interrupting the glazed perimeter. A second characteristic of the house is that it has no interior divisions made on site. We find only, towards the centre of the space, a wooden core which houses two bathrooms separated by a wardrobe and beside which the kitchen is also located- a so-called “American style”. SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities.

In 1997, he built a temporary visitor center east of the house and opened up the property for tours. Working in partnership, the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the Landmarks Preservation Council of Illinois (now Landmarks Illinois) were able to purchase the modernist icon. A 2008 flood damaged the core and required extensive repairs to the freestanding teak wardrobe. Given the understanding that upriver development and global warming have permanently increased the frequency of high water events at the Farnsworth House, flooding remains a threat to the site. Edith Farnsworth, a medical doctor based in Chicago, commissioned Mies to design a house on the Fox River, 60 miles outside the city. To give the occupant full advantage of the site’s natural beauty, Mies’s design featured an all-glass exterior.

A complex of designed, natural, and agrarian landscapes, it conveys a sense of the rural Midwest to visitors from around the world. Indeed, the now-famous house would not exist if the site hadn’t first inspired Edith Farnsworth and her architect, Mies van der Rohe, and later Peter Palumbo and the many artists and guests who gathered there in the last decades of the twentieth century. While visually minimal, the house‘s structure is extremely complex and interrelated. First conceived in 1945 as a country retreat for the client, Dr. Edith Farnsworth, the house as finally built appears as a structure of Platonic perfection against a complementary ground of informal landscape. The house faces the Fox River just to the south and is raised 5 feet 3 inches above the ground, its thin, white I-beam supports contrasting with the darker, sinuous trunks of the surrounding trees. The calm stillness of the man-made object contrasts also with the subtle movements, sounds, and rhythms of water, sky and vegetation.

Its interior and furnishings were all designed to provide a sense of connection to the landscape outside. Due to the Farnsworth House's location in the Fox River floodplain, the site often experiences low-level flooding. Despite the precautions taken in the design, waters have risen substantially inside of the structure multiple times in excess of FEMA 500-year flood levels. The house has a distinctly independent personality, yet also evokes strong feelings of a connection to the land. The levels of the platforms restate the multiple levels of the site, in a kind of poetic architectural rhyme, not unlike the horizontal balconies and rocks do at Wright's Fallingwater. The Farnsworth House addresses basic issues about the relationship between the individual and his society.

No comments:

Post a Comment